Solving a Viral Mystery

Experts Scramble to Trace the Emergence of MERS

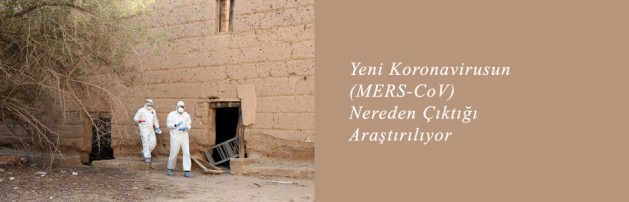

A field team from EcoHealth Alliance, Columbia, and the Saudi Health Ministry examined a  room taken over by bats in an abandoned village. They took samples for testing for the coronavirus causing Middle East respiratory syndrome. K.J. Olival/EcoHealth Alliance

room taken over by bats in an abandoned village. They took samples for testing for the coronavirus causing Middle East respiratory syndrome. K.J. Olival/EcoHealth Alliance

By DENISE GRADY

Published: July 1, 2013

As the scientists peered into the darkness, their headlamps revealed an eerie sight. Hundreds of eyes glinted back at them from the walls and ceiling. They had discovered, in a crumbling, long-abandoned village half-buried in sand near a remote town in southwestern Saudi Arabia, a roosting spot for bats.

It was an ideal place to set up traps.

The search for bats is part of an investigation into a deadly new viral disease that has drawn scientists from around the world to Saudi Arabia. The virus, first detected there last year, is known to have infected at least 77 people, killing 40 of them, in eight countries. The illness, called MERS, for Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, is caused by a coronavirus, a relative of the virus that caused SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which originated in China and caused an international outbreak in 2003 that infected at least 8,000 people and killed nearly 800.

As the case count climbs, critical questions about MERS remain unanswered. Scientists do not know where it came from, where the virus exists in nature, why it has appeared now, how people are being exposed to it, or whether it is becoming more contagious and could erupt into a much larger outbreak, as SARS did. The disease almost certainly originated with one or more people contracting the virus from animals — probably bats — but scientists do not know how many times that kind of spillover to humans has occurred, or how likely it is to keep happening.

There is urgency to the hunt for answers. Half the known cases have been fatal, though the real death rate is probably lower, because there almost certainly have been mild cases that have gone undetected. But the virus still worries health experts, because it can cause such severe disease and has shown an alarming ability to spread among patients in a hospital. It causes flulike symptoms that can progress to severe pneumonia.

The disease is a chilling example of what health experts call emerging infections, caused by viruses or other organisms that suddenly find their way into humans. Many of those diseases are “zoonotic,” meaning they are normally harbored by animals but somehow manage to jump species.

“As the population continues to grow, we’re bumping up against wildlife, and they happen to carry some nasty viruses we’ve never seen before,” said Peter Daszak, a disease ecologist and the president of EcoHealth Alliance, a scientific group that studies links between human health, the health of wild and domestic animals, and the environment.

Saudi Arabia has had the most patients so far (62), but cases have also originated in Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Travelers from the Arabian peninsula have taken the disease to Britain, France, Italy and Tunisia, and have infected a few people in those countries. Health experts are also worried about the Hajj, the Muslim pilgrimage that will draw millions of visitors to Saudi Arabia in October.

MERS has not reached the United States, but health officials have told doctors to be on the lookout for patients who get sick soon after visiting the Middle East. So far, more than 40 people in 20 states have been tested, all with negative results, according to Dr. Anne Schuchat, the director of the National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The illness can be spread by coughs and sneezes, or contaminated surfaces, and people with chronic diseases seem especially vulnerable. More men than women have fallen ill, possibly because women have been protected by their veils. A cluster of cases that began in a Saudi hospital in April ultimately involved 23 people, including several family members and health workers. One man infected seven people, each of whom spread the disease to at least one other person.

Regardless of where they emerge, new illnesses are just “a plane ride away,” said Dr. Thomas Frieden, the director of the C.D.C.

And while MERS is not highly contagious like the flu, he said, “the likelihood of spread is not small.”

Ailing Patients Most Vulnerable

In May, Saudi health officials asked an international team of doctors to help investigate the hospital cluster. One concern was that a number of cases were in patients at a dialysis clinic, and doctors feared that dialysis machines or solutions might be spreading the disease.

“It was pretty easy to figure out that couldn’t have been the case,” said a member of the team, Dr. Connie S. Price, the chief of infectious diseases at Denver Health Medical Center.

The patients’ records did not point to dialysis as the culprit, she said, and there were clear cases of transmission in other parts of the hospital that had no connection to dialysis.

Why, then, the outbreak among dialysis patients? The answer seems to be that they were older, chronically ill and often diabetic; diabetes can suppress the immune system’s ability to fight off infections. So, when one dialysis patient contracted MERS, others who happened to be in the clinic at the same were easy targets for the virus.

“Introducing it into a dialysis center gives it the perfect environment to spread among vulnerable patients sitting in open bays for many hours,” Dr. Price said.

Some health experts have suggested that MERS, like SARS, may fade away. The SARS outbreak erupted in early 2003, but ended by that summer. Much of the success was attributed to infection control in hospitals and also to eliminating animals like civet cats, which were thought to have caught the virus from bats and to be infecting people in markets where the civets were being sold live to be killed and eaten.

But Dr. Allison McGeer, a microbiologist and infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto who is also part of the team that studied the Saudi hospital outbreak, said there were no signs that MERS was going away.

“Absolutely not,” she said. “There are ongoing cases of disease acquired in the community. The first we know about is April 2012 in Jordan. There has been a steady and continuing number of cases.”

The fact that the disease has apparently emerged in geographically disparate places, with widely scattered cases in four Middle Eastern countries, also makes Dr. McGeer doubt that it is simply going to fizzle out.

Finding out where in the environment the disease is coming from might make it possible to tell people how to avoid it. Bats are the leading suspect, because they are a reservoir of SARS and carry other coronaviruses with genetic similarities to the MERS virus. Bats could be transmitting the disease directly to people, or they might be spreading it to some other animal that then infects humans. But what kind of bat? There are 1,200 species; 20 to 30 have been identified in Saudi Arabia.

Last October, to test the theory, a team of scientists from the Saudi Ministry of Health, Columbia University and EcoHealth Alliance began scouring Saudi towns near where cases of MERS had been reported, showing people pictures of bats and asking if they had seen any. They struck pay dirt when one man led them to an abandoned village in the southwest, said to be hundreds of years old. It was there, in the inky darkness, that they found a small room that had become the roost of about 500 bats.

The scientists set up nets to catch them when they flew out at dusk to hunt insects, then spent the night testing them for the MERS virus. The bats were let go after the testing.

The animals can weigh as little as four grams (one-seventh of an ounce), and a bat that size may have an eight-inch wingspan.

“They’re mostly wing,” said Kevin J. Olival, a disease ecologist with EcoHealth Alliance. “They’re little flying fur balls.”

It takes about 15 minutes to process a bat — to weigh and measure it, swab it for saliva and feces samples, and collect some blood and a tiny plug of skin from a wing for DNA testing to confirm its species. The specimens were then frozen and sent to the laboratory of Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, a leading expert on viruses at Columbia.

Bats do not much appreciate all this medical attention. They bite, and in addition to potentially carrying MERS, they may harbor rabies and other viruses.

“You’re wearing coveralls that cover everything — hoods, gloves, respirators, booties,” Dr. Lipkin said. “You’re all dressed, so you don’t have any contact with the animals. It’s night, but still very hot.”

Hundreds of bats have been tested, he said, but it is too soon to disclose the results.

From Animals to Humans

The team has also tested camels, goats, sheep and cats, which might act as intermediate hosts, picking up the virus from bats and then infecting people. One reason for suspecting camels is that a MERS patient from the United Arab Emirates had been around a sick camel shortly before falling ill. But that animal was not tested.

“If animals are acting as a reservoir, getting people sick, how would this happen?” asked Dr. Jonathan H. Epstein, a veterinary epidemiologist with EcoHealth Alliance.

If animals harbor the virus, does it make them ill? Do they infect people by coughing? Or do they pass the virus in urine or feces, and infect people who clean their stalls? The answers do not come easily.

“Camels are tough, let me tell you,” said Dr. Epstein. “They’re ornery. It takes a certain kind of person to be able to wrangle a camel. They’re strong, they’re fast, they bite really hard.”

The trick, he said, is to get the camel into a position that veterinarians call “ventral recumbency,” or lying on its belly. A very feisty camel may also have its legs tied together so it cannot run away or kick anybody. Then someone steadies its head, maybe with a harness, and holds its jaws open so a vet can reach in and out quickly with a cotton swab.

“They have a pretty big mouth,” Dr. Epstein said. “You try not to get bitten.”

So far, he said, “none of the animals we looked at were overtly sick.”

But Dr. Lipkin noted that the virus tests on livestock samples were not complete. Any specimens from such animals from other countries are considered a threat to agriculture in the United States because they could carry foot-and-mouth disease or other pathogens, and have to be screened first by the Agriculture Department before being released to research labs.

Testing may identify animal species that carry the virus, but that will not immediately explain why it has emerged now.

“The most common reason that wildlife viruses make the jump into people is that we do things that bring us and our livestock into closer contact with wildlife, such as the wildlife trade or agricultural intensification,” Dr. Epstein said.

And, said his colleague Dr. Olival, finding the animals that carry the disease is “not just an academic exercise.”

“It’s a way to inform public health measures,” he said, “to try to stop zoonotic diseases before they emerge into humans.”